The scent of jasmine lingers in the air as the first light of dawn touches the weathered stones of the Umayyad Mosque. Damascus, believed to be the world's oldest continuously inhabited city, awakens with a quiet dignity that belies its tumultuous past. In the Old City, where Roman columns stand alongside Ottoman-era merchant houses, the weight of centuries presses gently upon the modern visitor. This is not a place that shouts its history – it murmurs it through the rustle of fig leaves in courtyard gardens and the echo of footsteps on Byzantine-era flagstones.

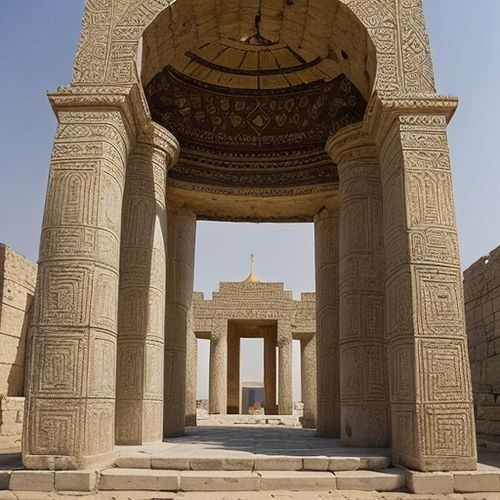

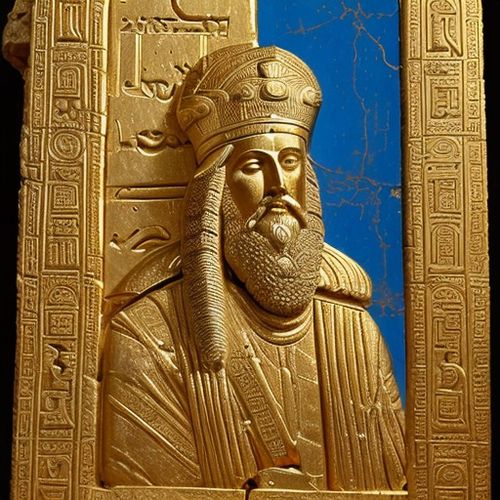

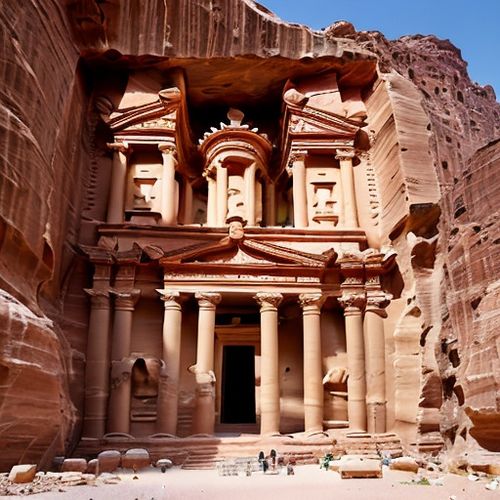

Walking through the labyrinthine souqs, one understands why Damascus has been coveted by empires across millennia. The Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Umayyads, Ottomans, and French all left their marks upon these streets. Yet what astonishes isn't the grand monuments – impressive as they are – but how seamlessly the layers of history intertwine with contemporary life. A Roman arch frames the entrance to a bustling spice market where vendors still measure saffron threads with brass scales unchanged since medieval times. The clatter of espresso machines in modern cafés blends with the call to prayer from minarets that have stood for twelve centuries.

The Souq al-Hamidiyah remains the pulsing heart of commercial Damascus, its iron-vaulted ceiling perforated by sunlight that dances across mounds of Aleppo soap and Damascene silk. Here, generations of merchants have perfected the art of bargaining over tiny cups of cardamom coffee. The sound of craftsmen hammering intricate silver patterns into wooden boxes creates a rhythmic backdrop to the commerce. These boxes, inlaid with mother-of-pearl in geometric patterns perfected during the Islamic Golden Age, represent one of Damascus's most enduring art forms – one that miraculously survives despite decades of economic sanctions.

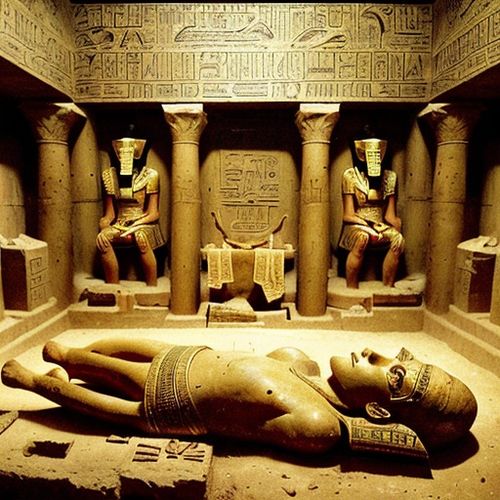

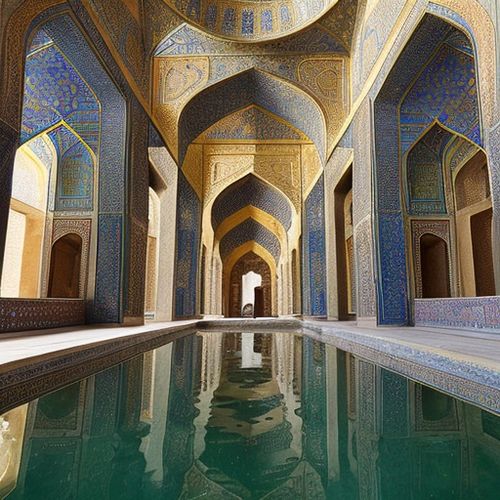

Beyond the markets, the residential quarters reveal another dimension of the city. Courtyard houses with central fountains and vine-covered trellises speak to an architectural tradition designed for both privacy and community. The Azem Palace, now a museum of arts and popular traditions, showcases this domestic architecture at its most refined. Its alternating black and white stone arches, cool marble floors, and fragrant orange trees create an oasis of tranquility that feels suspended outside of time. In these spaces, one glimpses the sophisticated urban culture that made Damascus a beacon of civilization when Europe languished in its Dark Ages.

Modern Damascus presents contradictions at every turn. Gleaming new restaurants serving molecular gastronomy interpretations of traditional dishes stand blocks away from centuries-old bakeries where flatbreads still bake against the walls of wood-fired ovens. Luxury cars navigate streets barely wide enough for donkeys, passing posters celebrating the Syrian army alongside fading advertisements for pre-war cinema releases. The city's youth gather in art galleries converted from Ottoman-era warehouses, debating politics over arghileh pipes while traditional oud music plays in the background.

Damascus University, founded in 1923 but occupying buildings with much deeper histories, continues to attract scholars from across the Arab world. Its campus buzzes with intellectual energy, though students now navigate challenges unimaginable to previous generations – from electricity shortages to the complexities of studying while supporting families devastated by war. Yet in lecture halls where medieval scholars once debated philosophy, today's students persist in their pursuit of knowledge, embodying the resilience that has defined this city through countless trials.

The surrounding Ghouta region, once Damascus's verdant agricultural belt, still supplies the city's markets with seasonal produce, though years of conflict have transformed this relationship. Farmers who once brought apricots and pistachios to the city gates now navigate checkpoints and fuel shortages. Yet the ritual of seasonal foods persists – the arrival of the first cherries in spring or the pressing of olive oil in autumn still marks the passage of time in Damascus as it has for millennia.

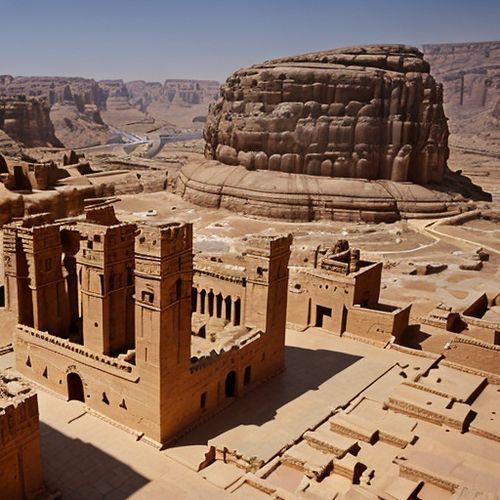

At sunset, when the light turns the Barada River gold and the minarets glow pink against the Qasioun Mountains, Damascus reveals its most magical quality – its ability to make the ephemeral feel eternal. In this moment, as the call to prayer echoes across rooftops where satellite dishes perch beside ancient water cisterns, the city's essential truth emerges: Damascus endures. Not as a museum piece frozen in time, but as a living entity that has absorbed countless shocks while retaining its soul. The stones may bear scars from recent conflicts, but they also contain the memory of every civilization that has called this place home.

To visit Damascus today is to witness urban resilience on a scale rarely seen in human history. The restaurants may have fewer customers, the museums fewer foreign visitors, but the spirit of the place – that alchemical mix of Arab hospitality, mercantile pragmatism, and intellectual curiosity – remains unmistakable. In the quiet corners of the Old City, where vine leaves cast shifting shadows on Ottoman-era walls, one can still hear the whispers of all the Damascenes who came before, adding another layer to the city's endless story.

By Grace Cox/Apr 28, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 28, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 28, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 28, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 28, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 28, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 28, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 28, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 28, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 28, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 28, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 28, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 28, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 28, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 28, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 28, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 28, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 28, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 28, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 28, 2025